Stop, Think, and Don’t React: Encouraging Parents to Be Proactive – Instead of Reactive or Confrontative – During Times of Conflict

Written By: Rebecca Thomas

Resource Creation By Bridget Morton

Design By Sunny DiMartino

“THIS IS NOT FAIR! YOU HAVE TO LISTEN TO ME! YOU WILL BUY ME A TICKET TO IRELAND OR ELSE!”

Brett let out a scream, spun on his heel, and pounded up the stairs to his bedroom, leaving Kim standing alone in the foyer. She heard him reach the center of his room, still yelling, and banging things around in his room, and knew he could stay that way for the better part of 20 minutes before he settled down.

This wasn’t the first time they’d had this discussion about his intense interest in visiting Ireland, and even eventually relocating there, and unless Kim figured out a more effective way to reason with her son, she knew it wouldn’t be the last. Ever since he started studying the origin of the Celts in his sophomore European History class last semester, Brett had been demanding with increasing vehemence that he be allowed to take a trip to Ireland. He had quickly become fascinated with the legends, mythology, and symbols associated with the region, and was convinced for some reason that he needed to visit their historical sites in person. Kim and her husband Joe had tried to reason with their son, explaining that a solo trip across the Atlantic was a bad idea on multiple levels. He was a minor, he didn’t have a passport, money was tight, and he needed to focus on his grades so he made it to be a junior, etc. They had even offered to take the trip as a family over a summer as soon as they could afford to, but Brett was implacable and extremely rigid. He needed to go to Ireland now. He’d even researched guest student programs online. Once when he was particularly “stuck” on the subject, he’d even gone so far as threatening to run away from home and stow away on an airplane if they continued to refuse his request.

In times like these, Kim tried to draw on her primary parenting resource—memories of her own mother, a woman who’d been kind but unfailingly firm. She’d never have tolerated this level of disrespect from any of her children and had been known to shut down an argument with one stern glare and the pointing of a forefinger. So far, though, those tactics failed in the face of Brett’s unrelenting arguments, and Kim was beginning to feel like a complete and utter failure as a parent. For his part, Joe did his best to offer his wife solace by pointing out that neither Kim nor her siblings had faced the challenges Brett did. Brett had special needs. Brett had been nearly four when Kim and Joe had adopted him, and the adoption consultants had explained that while complete information on his early life was lacking, it was known that he had experienced neglect and possible abuse over a period of time. The consultants mentioned that he might demonstrate some emotional and behavioral problems and that a positive and stable family environment would be very important. Sure enough, just after his fifth birthday, when it became clear that his frequent and extreme tantrums weren’t attributable any longer to his transition into an adoptive family, Brett had been formally diagnosed with Reactive Attachment Disorder (RAD) by a therapist who specialized in trauma disorders. The therapist had also mentioned that Brett’s inflexibility, emotional outbursts, and difficulty making friends was similar to Autism Spectrum Disorder. Nonetheless, the formal diagnosis was RAD, and the school eventually tested him and enrolled him in special education as a student with an “Emotional Behavioral Disorder” (EBD), and gave him an IEP.

Over the last decade, Kim and Joe had been able to sidestep most major blowouts by avoiding arguments, redirecting conversations, offering rewards, or removing privileges, but lately nothing they did seemed to curtail Brett’s angry and defiant behavior, particularly toward his mother, pushing Kim to the very limits of her patience. School behavior reports were mostly positive, but not at home. The more Brett fixated on ideas like this trip to Ireland, the more frustrated Kim became that he wasn’t being realistic, making her all the more determined to put her foot down.

That was what she was trained to do as a corporate attorney, after all. She knew how to fight back when cornered. Now, Kim’s every instinct was pushing her to storm upstairs and confront her son, tell him his tone was unacceptable, to knock it off, make him apologize, give it up on Ireland, ground him or take away TV privileges or... or... Kim sighed. Or what? She’d been through all of that yesterday, and the day before, and the day before. It hadn’t worked then, and it wouldn’t work now, and suddenly, she felt too tired even to try. She took her foot off the bottom step and turned away from the stairs, holding a hand to her forehead as she made her way down the hallway to the living room where Joe was watching TV.

“He’s at it again. For 30 minutes before he ran up to his room,” she said, picking up the remote and pressing the mute button.

“I could tell,” said Joe.

“I’m not sure how much longer I can continue walking away from him when he’s so angry and nasty to me,” Kim said.

Kim lowered herself onto the couch next to Joe, but when he put his arm around her, she refused to relax, keeping her body stiff and perched on the edge of the cushion, as if poised to get up. Joe sighed and removed his arm from her shoulders. “Honey, try to calm down,” he said. “You can’t get yourself worked up like this; it’s not healthy. You promised you’d try to let it go until we see this Dr. Williams, the behavior person.”

A

few weeks ago, Kim had gone in for a routine physical with her general

practitioner and discovered that her blood pressure had risen dramatically over

the last year. It hadn’t taken long for the doctor to determine the most likely

causes: anxiety and stress, and it was clear to her that Brett was the biggest

stressor in her life. Together, they’d devised a plan to try to help Kim get

back on an even keel. The first step had been for Kim to ask Brett’s school for

a recommendation for a psychologist who worked with kids like Brett. The school

social worker gave her the names of three local psychologists. One of them, Dr.

Williams, was also described as a “behavioral consultant” and after talking

with the receptionist they decided to make an appointment. She and Joe were now

scheduled to meet with Dr. Williams at 3 p.m. next Tuesday. “But I can’t just do

nothing!” Kim said, her fists tightening into balls on her lap. “Am I supposed

to just ignore it? Pretend everything’s fine?”

Joe shrugged. “You know that if you just give him a few minutes he’ll usually settle down, and then we all get back into our usual routine.”

“Our usual routine?” Kim spat. “You mean the one where you lose yourself in episodes of ‘The Mentalist,’ and “The Walking Dead” on Netflix and I’m left to verbally wrestle with Brett about whether or not he should be allowed to get on a plane alone and fly across the world? It’s absurd!”

As soon as the words left her mouth, Kim realized how cruel they sounded. Joe was the most patient, laid-back person she’d ever known, but even he hadn’t been able to keep from flinching.

“Oh God, Joe, I’m sorry. I didn’t mean that. I’m sorry. You just seem so together and mellow, and I feel like I’m losing it. I don’t know what to do anymore.”

The adrenaline that had been powering Kim for the last hour suddenly drained away, and she crumpled, letting her body go slack as she sank into the cushions next to her husband.

Joe put his arm back around her, and his voice was heavy when he replied. “I know. I do watch a lot of TV these days,” he said, his hand making slow circles on her upper arm. “I don’t know what to do about him either. Let’s see what Dr. Williams says next week. It’s all we can do right now.”

The next Tuesday, Kim and Joe arrived at Dr. Williams’ office promptly at 3:00 p.m. On the ride over, they’d agreed that no matter what the psychologist suggested, they would do their best to give it a shot. The most important thing in their minds was to create a more peaceful household environment for everyone. This constant friction was taking a toll on them all and their family’s stability was of utmost priority at this time.

“Good afternoon,” Dr. Williams said, giving them a reassuring smile and gesturing at the overstuffed sofa. “I know we talked briefly on the phone about your son, but tell me how I can help you.”

Kim spoke first.

“I’m not sure what to do anymore,” she said, her voice breaking with emotion. “I love Brett so much, I really do, and yet every day I feel more and more like a drill sergeant and not his mother. Brett has RAD. He’s also real uncomfortable socially and doesn’t have any friends. He doesn’t like to leave his room. If he does leave his room, he takes a stand on something, I fire back and tell him no, he retreats to his room, screaming at the top of his lungs, and we wind up in a never-ending battle of wills. He’s fifteen and yet it’s impossible to reason with him. Nothing seems to work. I have tried everything I know to do, and it only seems to increase his resolve to wage war with me.”

“I see,” said Dr. Williams. “That sounds stressful. No parent wants to feel like she’s constantly angry at her child, and no child wants to feel like his parent disapproves of him, particularly children like Brett with an attachment disorder, as you said. Kids with these challenges are often sensitive to signs of what they perceive as anger and hostility in others, and can react in some pretty difficult ways.”

“I know,” Kim said. “It breaks my heart to see my words hurting him, but in the heat of the moment I just lose all focus. I mean, logically, I understand—like right here and right now in this office—that if I react more calmly to Brett, that helps things not get worse. But that’s not easy to do.”

“So you’ve noticed that your own reaction to your son when he is upset influences how the entire conflict unfolds and ends, so either shortening or lengthening it?”

“Well, yeah. When I stay calm, things go better.” Kim looked over at Joe and he gave the doctor a knowing look. Both Kim and Joe laughed and then moved a little closer to each other on the couch. Dr. Williams smiled at the pair, pleased to be a part of their “A-HA!” moment.

“Well, that makes sense. I think many of us struggle between on one hand what we know is logical and rational, and balancing that with the other hand—which is what we feel emotionally and in our bodies—especially when in the moment,” said Dr. Williams, folding her hands on the desk in front of her. “And this is especially difficult, I might add, when we are parents and it has to do with our own children. Those can be very emotional times. I feel like I’ve learned quite a bit about your son today. Tell me more about how you two are doing.”

Kim

and Joe looked at each other, and then back at the doctor.

The doctor paused for a moment, looking from Kim to Joe, her face kind and open. “I want to tell you that your story is not unusual. I’ve heard it before and you’re really not alone, even though you might feel that way. I’ve also found that these kinds of situations may take a toll on family life. How would you describe your reactions, your own stress, and how you’ve been able to manage?”

Kim had to stifle a scoff. She crossed her arms over her chest. “I’m sorry, Dr. Williams, but is that really what we are here to talk about today? We made this appointment to talk about Brett’s behavior and how to fix it, not my mental health, or our marriage.”

Dr. Williams nodded. “Of course. I know Brett is your number one concern and why you’re both here today. You want things to go better at home between you and your son. In most cases I have found that a parent’s well-being and that of her children are not two separate things or issues. They’re intertwined. It’s all relational , I once heard a very smart person say. We have to remember that “the arrow goes back and forth” between all of us, including between children and their parents. It’s transactional. Each one affects the other and everything happens in a context and a system. You’ve mentioned that your son’s reactions affect your own. Have you seen any kind of a connection, or relationship, between your own stress level and how he may react or responds?”

Kim ground her molars together. Of course she was stressed, but who wouldn’t be? Her kid wouldn’t get off this Ireland kick, her husband was disconnecting, and she worked 50 hours a week. Is Dr. Williams saying this is my fault? Did they expect her to be some kind of saint? Kim opened her mouth to object, but Joe put his hand on her knee, and despite all her attempts to stay stoic, she felt a stinging rise behind her eyes. She looked up, trying to keep the tears from brimming over, but it was too late.

“Well, I can see how that might sometimes be the case,” Kim said, her voice cracking. “It’s just so hard. Joe is just so easy-going; he doesn’t let things upset him. I have more expectations of Brett.”

“That is not true,” said Joe, looking directly at Kim.

“Well, okay, maybe just different expectations then,” Kim said.

“Yes, our expectations for our son are different,” said Joe.

“Anyway, Joe tells me I should just try to relax and not feed into it, but when I’m in the midst of an argument with Brett, it doesn’t help to tell me to calm down. I already feel like a bad parent for allowing myself to get angry with Brett. I mean my child has a serious disability after all, so when Joe says something like that, I feel even worse.”

She swiped the back of her forearm across her cheeks, blinking to clear her vision. “I’m sorry,” she said. “I’m usually much more put together. This is hard.”

When Kim forced herself to look up at Dr. Williams, she saw that the woman was smiling gently. “There’s nothing to be sorry about, Kim. You’re a wonderful parent and doing your best in a very difficult situation.”

Kim sniffed hard, swallowing back more tears. Joe squeezed her knee.

Dr. Williams continued. “I’m thinking it would be a good idea to come up with a short-term plan right now, something to try to make things a little bit easier at home.”

“Okay,” said Kim. “I’m open to any ideas you have.”

“Me too,” said Joe.

“All right. Let’s take a look at these real tough times between you and your son. What seems to precede, or trigger, these intense arguments?” Dr. Williams asked. “Have you noticed any particular patterns? Certain times of day, people, situations, limit-setting, anything?

Kim thought for a moment before responding, running a mental catalogue of last week’s showdowns. “Well, now that you mention it, our really bad arguments seem to happen most often when Brett gets home from school.”

“Interesting,” said Dr. Williams. “I find that returning home after school can be a difficult time for a lot of kids. It is a big transition and kids with problems in flexible thinking often have a hard time ‘switching gears.’”

“I think so, yes,” Kim said. “It seems to be a pattern. Right after he walks in the door he will start talking to me about Ireland or whatever else is bugging him.” As she talked, a giddy lightness rose in her chest, like the feeling she got as a kid when the picture on the jigsaw puzzles she loved so much started to become clear. She glanced over at Joe and saw that he, too, looked excited, more alert, sitting up straighter and inclining his body slightly toward the psychologist.

“Okay, good, so we’ve learned something. These really intense arguments tend to occur right after school when Brett returns home. We need to remember also that ‘behavior is a form of communication,’ or expression. Given this pattern you’re describing, any ideas on what your son might be communicating or expressing through his behavior?” Dr. Williams asked.

“Well, yeah, he’s expressing that he’s pissed off that he can’t go to Ireland,” Joe said.

“His words say that, yes, but any idea what his words and behavior are trying to communicate or say? The underlying message?” Dr. Williams said, looking at each parent in turn.

“Well, I think he’s saying he’s feeling all wound up from school,” Kim said. “He talks a lot about things at school that bother him, too, like the kids. It’s not always just Ireland. We know school is not always a great place for him, and he doesn’t have many friends.”

“Okay, so I wonder if there’s something we can try so that your son’s transition to home from school is easier, he is calmer, and these intense arguments are not so disruptive to everyone in the house?” Dr. Williams said.

“I think he needs some kind of a distraction after school. Something not emotionally charged. Maybe an activity… I got it. Yes!” Kim eyes lit up as she spoke. “He loves it when we take bike rides together. We’d stopped for a while because of the sweltering heat, but I can definitely talk with him and see if we can try to go out right after he gets home and maybe ride for a half hour or so and see how it goes.”

“That sounds like something to try,” Dr. Williams said. Her smile was wider now, and her encouraging tone gave Kim the first real surge of hope she’d felt in months. “And the exercise will probably also help reduce your stress level. I really like this idea. Seems like it might work for everyone. Why don’t you give it a try and then in a few weeks we can meet again and see how it worked. In the rest of our time together today, I’d like to also go over some ways we can center ourselves, think through, and respond thoughtfully when kids are having meltdowns. I believe it might be helpful.”

The following day Brett came home and ran into the den, where Kim was finishing up some work emails.

“Mom!” he said, throwing his backpack onto the couch and striding across the room to stand beside her. “I was looking at those travel guides again on my phone today on the bus, and everybody says Ireland is best in the fall and the flights are cheap. We should buy tickets now, before the prices go up.”

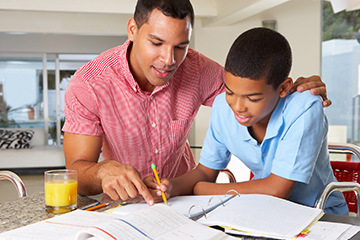

Brett started to bend over Kim’s shoulder, preparing, Kim knew, to take the mouse and steer her to an airline site. But before Brett’s hand reached hers, she swiveled in her seat and stood up, making sure to keep her face calm. She looked in her son’s darting green eyes and smiled. “I’ve been thinking,” she said brightly. “Why don’t we go for a bike ride? We can get some fresh air and talk about what else you learned today. This might be something to try every day after school for a while. I know I could use the exercise.”

There was a pause as Brett’s familiar train of thought slowed. He furrowed his eyebrows and tilted his head.

“Why would I want to do that?” he asked as he studied her, his voice uncertain.

Kim’s pulse quickened. She could feel her reprimand rising, could hear herself getting ready to bend Brett to her will. Then she closed her eyes for a fraction of a second and swallowed hard. As she paused, she could hear Dr. Williams’ words play over in her mind: “S top (take a deep breath, pay attention to my nonverbals), Think (I’m okay, my goal is to stay calm and not have this turn into a huge conflict, to tell him calmly what I’m thinking and why), and then Act.”

As these words reverberated through her head, Kim took a deep breath, relaxed her shoulders, smiled gently, adjusted her stance, and allowed her arms to relax at her sides.

“Well, it’s a beautiful day, and I know after school has been a rough time of the day for both of us lately so I thought a bike ride could help us both blow off a little steam,” Kim said. “Besides, when was the last time we went on a bike ride together?”

Kim held her breath while Brett stared. Then he said slowly, “I guess it has been a while. I haven’t gotten a chance to use those spoke lights I got for my birthday.” His face, which had been scrunched in suspicion, began to relax. “And I haven’t even told you about chemistry. Ms. Malone brought liquid nitrogen to class, and we all got to freeze something! And next week in biology we get to dissect cow eyeballs!”

He grinned at Kim, and for a moment, she wavered on the cusp of tears. Not the tears she usually shed, those of failure and frustration, but tears of sheer relief. And then the moment passed. She grinned back at her son.

“That sounds awesome!” Kim said. “I can’t wait to hear more.”

As she followed her son to the garage, her step felt a bit lighter. This simple exchange already felt like a step in the right direction. She was beginning to feel more relaxed. He seemed more relaxed. The arrow really does go back and forth, she thought. She looked forward to sharing this small, yet important, victory with her husband when he arrived home that evening.

This story is part of a series based on the experiences of educators, parents, and the staff of Genesee Lake School, a nationally recognized provider of services for students with special needs. GLS is part of MyPath, an employee-owned family of companies whose mission is to make a difference in the lives of people with disabilities.

Sign Up to Receive New Posts

We promise not to spam you or share your information with anyone. And you can unsubscribe at any time . . . although we hope you stay a while!