Children with Prader-Willi Syndrome: Impulse Control Issues and Dishonesty

By Alison Hennessee

Resource Creation By: Maureen Batty

Design By: Sunny DiMartino, Christy Bui, Analee G. Paz

Ben was riding buses in the middle of the night.

He’d been doing it for weeks before I found out. Looking back, it seems I should have known sooner, but it’s easy to blame ourselves for the past—easier than facing the situation, easier than asking what now, and certainly easier than answering that question.

Ben was 13. We didn’t know he had Prader Willi syndrome—it was the early 1990s, and most physicians didn’t even know that the rare genetic disorder existed—but we knew absolutely that something was wrong and had been since he was born. He was a small baby, with a poor sucking reflex and almond-shaped eyes that wandered off to the periphery instead of gazing into mine. In his early months, he was thin, and I worried constantly that I was doing something wrong, that he wasn’t getting enough milk, that my baby boy was going to starve. I was so relieved when, as a toddler, he began eating with gusto, even begging for seconds. “Ben loves vegetables!” I would laugh to friends. The truth was that Ben loved everything. By the time he was 13, I’d lost track of the number of times the pediatrician had told me that Ben needed to lose weight.

“I’ve got to be blunt, Nancy,” Dr. Sparkman said at our last visit, after asking Ben to wait for us in the other room. “He’s obese. There’s no other way to put it. You have to make him stop eating so much.”

I didn’t say anything. There was nothing to say that I hadn’t already said many times before, though no one seemed to hear me. I knew Ben needed to lose weight. He was under five feet tall and weighed close to 150 pounds. But he also struggled with intellectual, speech, and behavior problems, had delayed motor development, and was lately covered in scabs from where he picked at little bumps on his skin. Ben was obese, yes. But there was something else going on, too, and no one could tell us what it was.

Since Ben was in kindergarten, the measures we’d taken to curb his eating had become more and more drastic. In the early days, we’d tried telling him what any parent would say to a child who wants more snacks than he needs: We’d all like to eat 10 cookies sometimes, but that isn’t good for our bodies. I thought he’d eventually learn to control his eating.

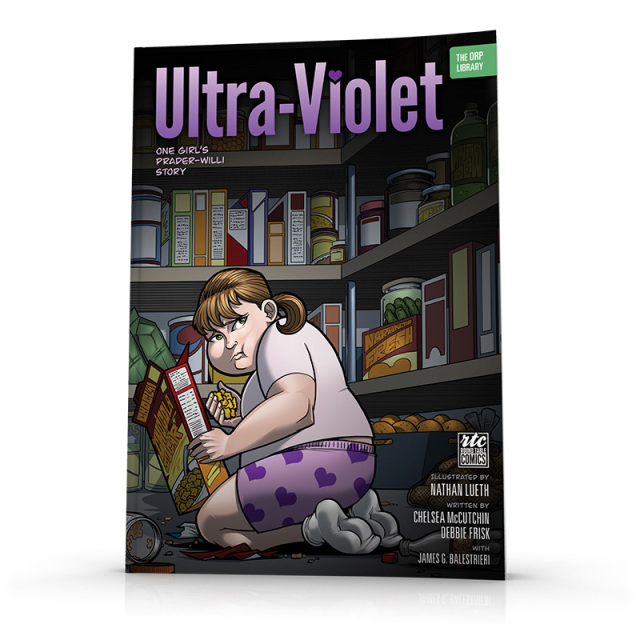

Instead, he learned to sneak food. When Ben was very young, it had been a regular occurrence to find him sitting on the pantry floor, surrounded by clumsily torn pretzel bags and the glitter of dozens of discarded chocolate foils. After being caught and scolded again and again, Ben made sure to scuttle out of the pantry just before I arrived.

Then, food disappeared. We’d find the remnants—wrappers and boxes and peels and rinds—stuffed under Ben’s bed or wedged behind a bookcase in the hall. On some nights, I would go downstairs for a glass of water and there would be Ben, hunched over a gallon carton of ice cream, his face eerily pale in the light from the open freezer. One time, he ate two loaves of frozen bread dough from Costco. When I discovered a nest of Snickers wrappers in his backpack, he blamed bullies. I knew his story was a lie, but the bullying wasn’t—he had been jeered for years, called “retard” or, worse, the moniker “Retardo Tub-of-Lardo.” Kids refused to play with him. He was never invited to birthday parties, and no one from school came to his. Our attempts to enlist the help of everyone from bus drivers to the principal created no lasting change. So the plausibility of Ben’s story, the way it played on my concern, made the lie all the more hurtful.

Life with Ben had always been challenging, but until he was 13, we were able to keep our son safe and the chaos to a minimum. This changed drastically at the beginning of Ben’s eighth-grade year. First, I discovered that my rainy day fund was empty. It wasn’t much, not real savings, just a collection of small bills that I’d socked away for those unexpected times you need cash—the babysitter needs an extra five or a local boy offers to mow your lawn. I kept the money in a tin that had once held jelly beans. The irony wasn’t lost on me—Ben probably opened it hoping it was filled with candy. I convinced myself that my husband Matt must have used the money without telling me, or that maybe I had spent it but didn’t remember. Shortly after that, Matt found a pile of food wrappers in the gutter half a block from our house. It was suspicious, but Ben denied knowing anything about it, and after all, there’s trash everywhere; it didn’t prove anything.

The call from the police at two a.m. was much harder to deny.

“Mrs. Thompson? We have your son, Ben. You’ll need to come down to the station.”

He’d been caught shoplifting snacks at a gas station several miles from our house. The money he’d taken from the tin in the closet was enough for a few nights of bus fare and several shopping sprees, but it ran out before Ben’s hunger did. All I could think was what if? What if someone had kidnapped him? What if the cashier had been afraid of Ben and used a weapon? What if Ben had fought the police, the way he did sometimes when he was angry or scared, and they had been forced to subdue him?

That night is a mixture of blurred scenes with dampened audio and images so sharp and clear they still pierce me. One of those images is Ben huddled in a folding chair at the police station, his face pink and tear-stained, a slash of strawberry ice cream across his t-shirt. Sitting there, he looked, for all his bulk, like a very small boy.

As a parent of a child with Prader Willi syndrome, you may find situations like Ben’s all too familiar. Almost every family that struggles with PWS has stories about their child’s food seeking efforts, which often include deception and stealing. These efforts have nothing to do with the child’s manners or morals, nor your parenting skills. Rather, the social maladjustment is driven by a rare and paradoxical disorder that impacts development broadly and results in behavioral efforts and the motivational drive to reduce hunger.

If you, too, have been struggling to keep your child healthy and safe and feel you are running out of ideas, there are lifestyle and home remedies you can consider. Some of these measures may feel cruel when you first enact them, and your child may become agitated, even furious, about your restriction of his or her access to food. But there’s nothing unkind about keeping your child safe. The internal regulator most of us have that allows us to know what kind of food and how much we need is broken in your child with PWS, and he or she needs outside help to impose regulations. The goal is not to please your child but to help him or her find and maintain health. There’s no such thing as doing it perfectly; there is only doing your best with love.

*Ben’s story is based on interviews with numerous parents of children with PWS. His struggles reflect the daily and long-term challenges of those with PWS and their families.

Sign Up to Receive New Posts

We promise not to spam you or share your information with anyone. And you can unsubscribe at any time . . . although we hope you stay a while!